Art Never Stops: A Resilient Africa Confronts Covid-19

Players in the African art scene discuss how they’re handling the effects of Covid-19 and how working amidst radical conditions is nothing new for the African continent

Many will agree that some of the most interesting art flourishes during difficult times. Art, in the midst of upheaval, often becomes a necessity. It is a way to express anger, frustration and critique society. As the world continues to be ravaged by Covid-19, art is the battle sword for hope.

The African continent, while late to the Covid-19 outbreak, is one of the world’s most vulnerable regions to the virus. On April 7 the World Health Organization (WHO) stated that the number of Covid-19 cases had now risen to more than 10,000, claiming more than 500 lives on the African continent. Coronavirus, while slow to reach Africa, has grown exponentially. A total of 52 countries have reported cases, with the nations of South Sudan and Zimbabwe most at risk, the statement read. As a result, several African nations went into various degrees of lockdown from the end of March.

As health experts warn, Covid-19 in Africa has the potential not only to cause thousands of deaths, but also to foster economic and social devastation. What happens then to the African art market that has been thriving in recent years, booming as many would say? How are galleries, institutions and artists adapting to current the zeitgeist, however temporary?

Tactics For Survival

While larger, more established galleries on the continent have more means to weather out the socio-economic storm inflicted by Covid-19, smaller galleries are finding it more difficult. “Survival is a huge concern,” said founder of Circle Art Gallery in Nairobi Danda Jaroljmek. “I don’t know how many small galleries will survive if this goes on for over three months. The loss of income from walk-in clients, art fair sales and the cancellation of exhibitions—I don’t know how we will survive if it goes on too long,” she added. “Circle has six full- time staff, including our driver and cleaner, myself, the gallery manager, administrator and accountant who are all receiving full salaries and are reliant on the money.”

However, younger and smaller-sized galleries like South African Guns & Rain are better equipped due to their already expansive digital platform. “Interestingly, Guns & Rain started as an online-only gallery back in 2014, one of the first to do so in Africa,” said owner Julie Taylor. “So, the prospect of being online-only is perhaps less daunting for us than other galleries, even though we now have a physical space in Johannesburg too.”

The ones who are most vulnerable are the younger artists and gallery staff. While some galleries have no choice but to make cuts, others have ramped up their support. “Ahead of our regional lockdowns, we acted fast to order materials for our artists in Zimbabwe and Namibia, so that they would have enough to work with in the coming weeks,” added Taylor. “Similarly, despite modest budgets, we made advances to our small staff and some artists so that they could buy materials and food ahead of lockdown.” Like other spaces, Taylor said speaking regularly via video calls is not only vital to keep the gallery functioning and the work selling, but also “for combating the isolation and anxiety that the pandemic is creating.”

Africa: Always A Rough Terrain

Yet Africa, with its ongoing political tensions and socio-economic issues, its remnants of centuries of colonialism haunting the establishment of present day structures, has always been a challenging terrain to navigate. Many artists and gallerists say they are accustomed to working under challenging conditions. The current lockdown for many has not proved to be as shocking as it has for its western or more “developed” counterparts.

“I take issue with the phrase ‘not much support, and means for hope,” said Valerie Kabov, Director, First Floor Gallery in Harare, Zimbabwe. “There is a tendency to always see Africa as a space for disaster and hopelessness. On the contrary, we are in fact in a space of innovation and much better positioned to address radical new circumstances than art sectors of the developed world.”

“We are not burdened by heavy operation costs, legacy infrastructure and burdens of over-regulation and conservatism of the older generation which makes implementation of new ideas difficult,” she continues. “Most of us in Africa have started galleries in impossible situations and in impossible environments, so the notion that we don’t have means for hope is entirely untrue.” Kabov, like other galleries on the African continent, wishes now that galleries to operate as collective organizations rather than as merely profit-oriented businesses. “We are able to call on all the resources in the organization to help implement projects of support and to effect projects of support,” she adds. “This includes using our resources to provide subsistence income, where necessary, medical care, transport and art materials.”

A Growing Lack Of Resources

But what happens when resources are scarce? Picha, an art center run by a group of artists based in Lubumbashi, DRC, is now closed. The organization supported the Lubumbashi Biennale in 2008 and was also behind the most recent one which culminated in November 2019. “We are trying to reinvent ourselves digitally very quickly,” said Gabriele Salmi, a member of Picha. “Many of the artists are suffering and many are finding it hard to put together one meal per day right now. We are all joining hands to help each other and provide food.”

As of March 26, authorities in DRC closed air, land, sea and ports nationwide. Public gatherings were banned and markets, bars and restaurants are to remain closed until further notice. Most schools and universities will remain closed through at least April 17. Most recently, on April 6, authorities imposed a lockdown in the Gombe municipality of Kinshasa until April 20. Nearly all of the infections, 267 and 22 deaths, have occurred in the country’s capital of Kinshasa.

In South Africa, Johann Rupert launched the Sukama Relief Program, a R1bn ($55,526,948) Covid-19 relief fund. Artists registered as businesses were eligible to apply. However, on April 7, it was announced that the fund would be closed temporarily after receiving R2.8bn in applications. It still has yet to be proven how many South Africans are benefitting from the program and as of yet, there are no wide-sweeping funds or loans to help the arts community in South Africa.

Art Never Stops

On the artist front there’s no doubt that artists will continue creating their work. The problem lies in how they will sell and via what means? For a new market, one that has peaked the interests of collectors in Europe and North America and that has as well a growing group of collectors on the continent itself, the socio-economic effects for the young African art scene could be devastating.

“The African art scene is very much continuing but from home,” said Oumy Diaw, a PR specialist based in Dakar, Senegal. “Of course, there’s a bit less of a buzz. Digital now is the new art tool. Everyone is online now,” she continues. “We see more artists posting their work online which is great because before artists from Senegal were dependent on exhibitions or gallery semi-representation 1semi-representation meaning that the artists in Senegal don’t have exclusive solid representations within the country. In most case, galleries use them for opportunities of selling but not building their career, which obviously force the artists to rely mostly on themselves and now, they are doing it on their own. Many artists are producing new work while in confinement. It’s a time for them to concentrate all their efforts on their art. The good news is that we will have more art that will come out of this. Some artists have even created artwork inspired by Covid-19 health crisis.”

Inspired by the current situation where abandoned street scenes are now the normal sight in typically overcrowded African city centers, Senegalese artist Fally Sene Sow, one of the artists selected for Dak’Art, has been making expressionistic paintings of empty streets in disarray, with their vibrantly colored awnings now starkly in view.

The big event on the horizon was the 14th edition of the Dakar Biennale, Africa’s oldest and most prestigious art biennale scheduled to take place from 28 May to 28 June and now postponed until the end of the year, with the dates still to be decided.

At midnight on March 23 Senegal’s President Macky Sall instituted a curfew from 8pm until 6am for 30 days, shutting down all shops and businesses operating in the country, and halted all commercial passenger flights until April 17. Senegal, along with Gambia, closed their borders for 21 days to contain the spread of the virus. Nigerian-American painter Kehinde Wiley’s first Black Rock Residency, which kicked off in June 2019 and runs until April 2020 in Dakar, continues. However, the last artist that was supposed to arrive one week ago was unable to and a Nigerian writer in the residency will need to stay on until flights reopen.

“Everyone who enters into the compound has to wear the mask and be clean,” said Zohra Opoku, a Ghanaian-German artist in the residency. “We are under curfew so need to be back by 8pm. We hope this won’t go on longer than two weeks because we were looking forward to discovering more of Dakar and Senegal. But even though we are on lockdown I have to remind myself how grateful I am to have this studio.”

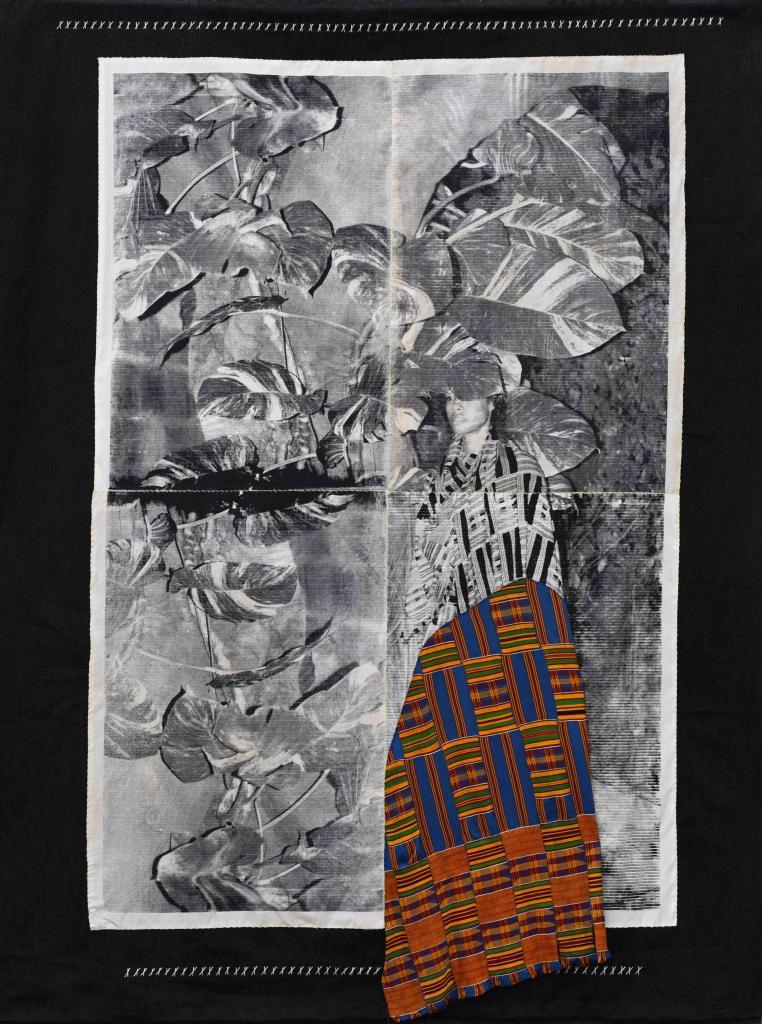

* First work in the slideshow in the article is a work by artist Zohra Opoku, One of Me I, 2017. Courtesy of the artist and Mariane Ibrahim gallery.

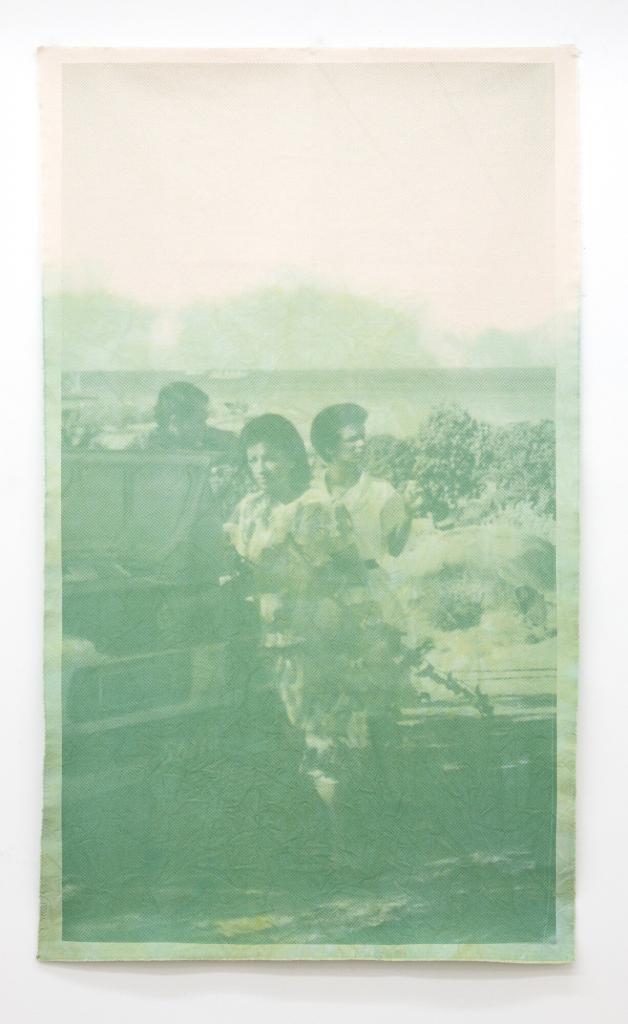

**Second work in the slideshow in the article is a work by Tahir Karmali, Paradise #2, 2019. Acrylic screen print on organic natural dip-dyed canvas. 167.6 x 99.1 cmCourtesy of the artist and Circle Art gallery.